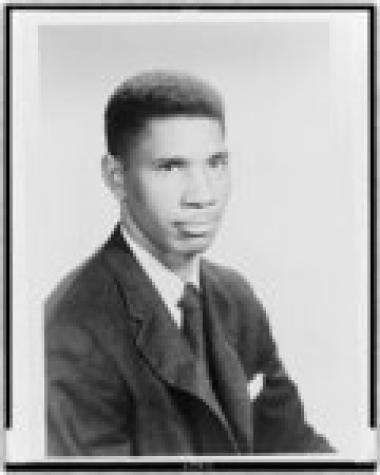

On June 12, 1963, civil rights leader Medgar Wiley Evers (1925–1963) was assassinated in the doorway of his home in Jackson, Mississippi—shot in the back after returning home from a meeting. As one of the first martyrs of the civil rights movement, his death changed the tone and the course of the movement.

Born in Decatur, Mississippi, Medgar was inducted into the U.S. Army and fought at the Battle of Normandy during World War II. After the war, he graduated with a degree in business administration from Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Alcorn State University, Lorman, Mississippi) where he married Myrlie Beasley, settled in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, and worked in the insurance business. He and his brother Charles worked together to build local affiliates of the NAACP in Mound Bayou and surrounding areas of the Delta. They organized boycotts of gas stations that denied Black people access to their bathrooms. When Edgar moved to Jackson in 1954, becoming Mississippi's first NAACP field secretary, he traveled throughout the state recruiting members, organizing voter registration drives, coordinating economic boycotts, and fighting for the enforcement of school desegregation laws. The enforcement of desegregation laws was personal to him because he was denied admission to the University of Mississippi Law School, although the U.S. Supreme Court 1954 decision had ruled segregation unconstitutional. Later, in the early 1960s, his efforts to have James Meredith admitted to the University of Mississippi brought him much attention and much-needed federal help. Meredith was admitted, but riots ensued, two people died, and hatred among White people toward Medgar increased.

Medgar was buried with full military honors ar Arlington National Cemetery and later that year was awarded the NAACP Spingarn Medal posthumously. His brother Charles continued Medgar's civil rights work, as did his wife, Myrlie Evers-Williams, who served as the first woman to head the NAACP (1995–1998).

Byron De La Beckwith was charged with killing Medgar, but in two trials in the 1960s the all-White juries failed to reach a verdict. In a third trial in 1994—31 years after Medgar's murder—Beckwith was found guilty and was sentenced to life in prison.

This tribute from The Mississippi Writers Page says much about Medgar Evers: "The legacy of Medgar Evers is everywhere present in the Mississippi of today. This peaceful man, who had constantly urged that 'violence is not the way' but who paid for his beliefs with his life, was a prominent voice in the struggle for civil rights in Mississippi. Many tributes have been paid to Medgar Evers over the years, including a book by his widow, For Us, the Living, but perhaps the greatest tribute can be found in changes noted in Mississippi Black History Makers: 'Ten years after Medgar’s death the national office of the NAACP reported that Mississippi had 145 black elected officials and that blacks were enrolled in each of the state’s public and private institutions of higher learning.... In 1970, according to statistics compiled by the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, more than one-fourth or 26.4 percent of black pupils in Mississippi public schools attended integrated schools with at least a 50 percent white enrollment. When Medgar died in 1963, only 28,000 blacks were registered voters. By 1971, there were 250,000 and by 1982 over 500,000.'"